As we look forward to the report next week, the monthly-repeating theme is ‘when will the tariff effect show up?’ The answer, so far, is ‘not yet,’ but economists who had forecasted the end of life as we know it when the Trump tariffs went into effect have been befuddled.

I’ve already admitted in this column that I was educated in the tradition of ‘tariffs bad,’ but that over the years Trump’s insistence otherwise has made me carefully re-think which ways tariffs are truly bad, and which ways they’re not so bad. Naturally, if tariffs were uniformly bad, which seems to be the orthodoxy, then it would be really hard to explain why almost every country levies tariffs.

Maybe forty years ago, we could blame the benightedness of those poor policymakers in other countries, who clearly just didn’t understand how bad tariffs are. But now? Heck, all someone in one of those countries needs to do is ask ChatGPT ‘are tariffs bad,’ and they’ll learn!

… Conclusion: Tariffs can be useful tools in specific, limited circumstances — like protecting vital industries or responding to unfair trade practices. But long-term, high or broad tariffs often do more harm than good, especially in highly interconnected global economies. (ChatGPT, July 9, 2025 query ‘Are tariffs bad’)

But it seems every country has these specific, limited circumstances. It’s evidently only bad when the US imposes tariffs. And that is what made me ask whether maybe there is some nuance. My 2019 article was really good, I thought.

Even as there has been some small movement in the economintelligencia, though, about whether tariffs are all bad there has been very little movement in the notion that they are clearly inflationary. No doubt, implementing a tariff will raise prices at least a little, but how much is the important question.

And regardless of that answer, tariffs are a one-time adjustment to the price level even if that effect is smoothed over a period of time. (This is why it’s weird to hear Powell say that the Fed can’t ease because they’re waiting to see the effect of the tariffs on inflation. That’s economic nonsense. The Fed can’t possibly believe that keeping rates high is the proper response to a one-time shock.)

On this question, I thought I’d share something I wrote in our Quarterly Inflation Outlook from Q1 (in mid-February), in which I roughly estimated the effects of a 20% blanket tariff. I know the answer isn’t “right,” because that’s the wrong question – there isn’t a 20% blanket tariff.

But I undertook the estimate to get an idea of the relative scale of effects. (I included in the piece some parts from that 2019 article mentioned above, because I’m not above stealing from myself!) I will add some concluding thoughts after this ‘reprint’ from our QIO, which, by the way, you can subscribe to here.

Tariffs as a Tool to Promote Domestic Growth and Revenue

In the President’s view, the fact that the U.S. has a very low tariff structure compared to the tariffs (and arguably VAT taxes) that other countries place on U.S. goods is prima facie evidence that the U.S. is being taken advantage of and treated unfairly on world markets. The U.S. has, for the better part of a century, been the main global champion of free trade, and this tendency accelerated markedly in the early 1990s (as the familiar chart below, sourced from Deutsche Bank, illustrates well).

The effect of free trade, per Ricardo, is to enlarge the global economic pie. However, in choosing free trade to enlarge the pie, each participating country voluntarily surrenders its ability to claim a larger slice of the pie, or a slice with particular toppings (in this analogy, choosing a particular slice means selecting the particular industries that you want your country to specialize in).

Clearly, this is good in the long run – the size of your slice, and what you produce, is determined by your relative advantage in producing it and so the entire system produces the maximum possible output and the system collectively is better off. To the extent that a person is a citizen of the world, rather than a citizen of a particular country – and the Ricardian assumption is that increasing the pie is the collective goal – then free trade with every country producing only what they have a comparative advantage in is the optimal solution.

However, that does not mean that this is an outcome that each participant will like. Indeed, even in the comparative free trade of the late 1990s and 2000s, companies carefully protected their champion companies and industries. Even though the U.S. went through a period of being incredibly bad at automobile manufacturing, there are still several very large U.S. automakers.

On the other hand, the U.S. no longer produces any apparel to speak of. In fact, the only way that free trade works for all in a non-theoretical world is if (a) all of the participants are roughly equal in total capability, and permanently at peace so that there is no risk that war could create a shortage in a strategic resource, or (b) the dominant participant is willing to concede its dominant position to enrich the whole system, rather than using that dominant position to secure its preferred slices for itself and/or to establish the conditions that ensure permanent peace by being the dominant military power and enforcing peace around the world. We would argue that (b) is what happened, as the U.S. was willing to let its own manufacturing be ‘hollowed out’ in order to make the world a happier place on average.

The President (and many of those who voted for him) feel that (b) is inherently unfair, or has reached extremes that are unfair to U.S. citizens. Essentially, the President is rejecting the theoretical Ricardian optimum and pursuing instead a larger slice for his constituents. This is where reciprocal tariffs (where the U.S. matches the tariff placed on its exports by a trading partner, with a tariff placed on the imports of that product from that trading partner) or blanket tariffs (where the U.S. imposes a tariff on all imports of a product irrespective of source – e.g. aluminum – or on all imports from a given trading partner) come in.

Blanket tariffs are good for domestic growth [1] but definitely increase prices for consumers. How good they are for growth, and how much prices rise, depends on how easily domestic untariffed supply can substitute for the imported supply, and also on whether your country is a net importer or exporter, and how large the export-import sector is in terms of .

Because this is an inflation outlook, let’s make a very rough estimate of the impact on the overall domestic price level of a blanket 20% tariff (such as the one Treasury Secretary Bessent has proposed). We suppose the average elasticity of import demand in the U.S. to be 3.33 [2] and the elasticity of export supply to be 1.0 [3]. In that case, the incidence of a tariff falls about 23% on consumers: [1.0 / (3.33+1.0) ]. So, for a 20% tariff, prices for the imported goods would be expected to rise about 4.6% (20% tariff x 23% incidence). However, imports only account for about 15% of US GDP, which means the effect on the overall price level would be 15% x 4.6% = 0.69%.

So, for a 20% blanket tariff on imports, Americans should expect to see a one-time increase in the overall price level of something on the order of 0.7%, smeared over the period of implementation. This is not insignificant, but it is also not calamitous. It does affect our estimates for 2025 and 2026 inflation, shown in the “Forecasts” section (somewhat less than 0.7%, because we do not expect a blanket tariff but rather reciprocal and targeted tariffs). Also note that the retaliatory tariffs on US exports have no direct effect on domestic prices, so that whether or not trading partners retaliate is irrelevant to an analysis of first-round effects, anyway.

Thus my wild guess back in February was that a 20% blanket tariff would result in a bit less than 0.7%, smeared out over 2025 and 2026. That doesn’t answer the ‘timing’ question, but the delays in implementation (so as to not affect Christmas 2025 prices of the GI Joe with the Kung-Fu Grip) and the importer/retailer initial reaction to try and absorb as much as possible for optics – presumably, easing price increases into the system later – mean that it shouldn’t be shocking that we haven’t seen a big effect yet. My point in the above calculation, though, is that we really shouldn’t expect to see a big effect, regardless.

For what it’s worth, the Budget Lab at Yale estimates that currently “the 2025 tariffs to date are the equivalent of a 15.2 percentage point increase in the US average effective tariff rate,” so if we take my 0.7% guess for 20% then we would be looking closer to 0.5% in total. And in fact, lower even than that since the 15.2% average will have less impact than a 15.2% blanket tariff, assuming that the tariffs will be highest where domestic substitution is easier.[4]

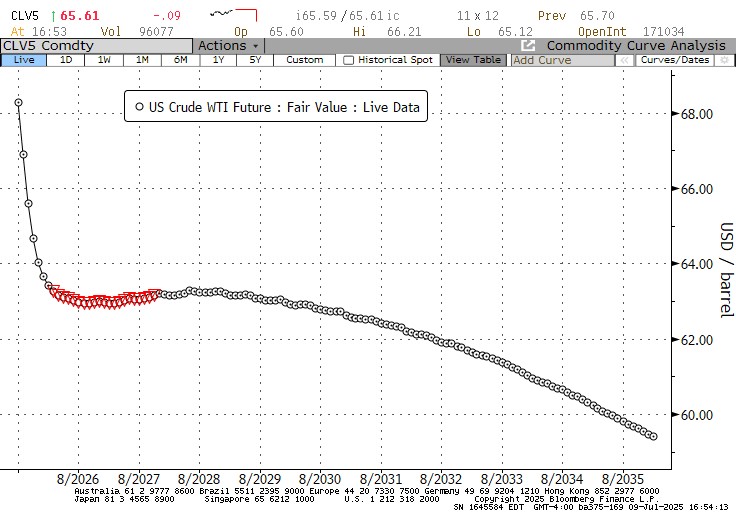

Wrapping this up, let me make one final observation. Current year/year headline CPI inflation is 2.35%. The inflation swaps market, specifically the market for ‘resets’ where you can trade essentially the forward price level, currently suggests that traders expect y/y inflation to rise to 3.29% over the next six months: almost 1 full percentage point from here. But that actually flatters what the market is pricing, because the shape of the energy curves suggests that rise is being dragged about 20bps lower by the implied moderation in energy prices (give me a break, inflation traders: I’m doing this in my head).

So, the market is pricing core inflation peaking about 6 months from now, about 1.2% higher than it currently is. Not all of that is the effect of tariffs; some is due to base effects as the very low May, June, and July 2024 numbers roll off of the y/y figure. But if we get that result, you can be sure that economists will put most of the blame on Mr. Trump, while Mr. Trump will put most of the blame on Mr. Powell. Either way, I think the interest rate cuts that the President would prefer are unlikely unless growth takes a significant stumble.

Citations:

[1] …but bad for global growth! There is no question that unilaterally applying tariffs to imports is bad for all suppliers/countries providing those imports. If Ricardo is right, the overall pie shrinks but the domestic slice gets larger…at least for the dominant players who already have a large slice. If everyone raises tariffs in a trade war outcome, the less-productive countries suffer the most loss of growth and the most-productive countries likely still benefit. But prices rise for all.

[2] Kee, Nicita, and Olarreaga, “Estimating Import Demand and Export Supply Elasticities”, 2004, Figure 5, available at http://repec.org/esNASM04/up.16133.1075482028.pdf. Your answers may vary!

[3] Estimates are wildly all over the map, depending on the exporting country and the product. In general, the smaller the country, the more price-inelastic it is. We chose unit elasticity here (a 1% increase in price cause a 1% increase in the quantity supplied) just to be able to get a rough guess.

[4] The Budget Lab at Yale also estimates the effect on PCE inflation of a whopping 1.74%. They must be really surprised at the impact so far.